In the 1960s, jogging was not something people did. But in his own quiet way, Emil Garippo has been at the frontlines of change, challenge and progress in America for almost 100 years.

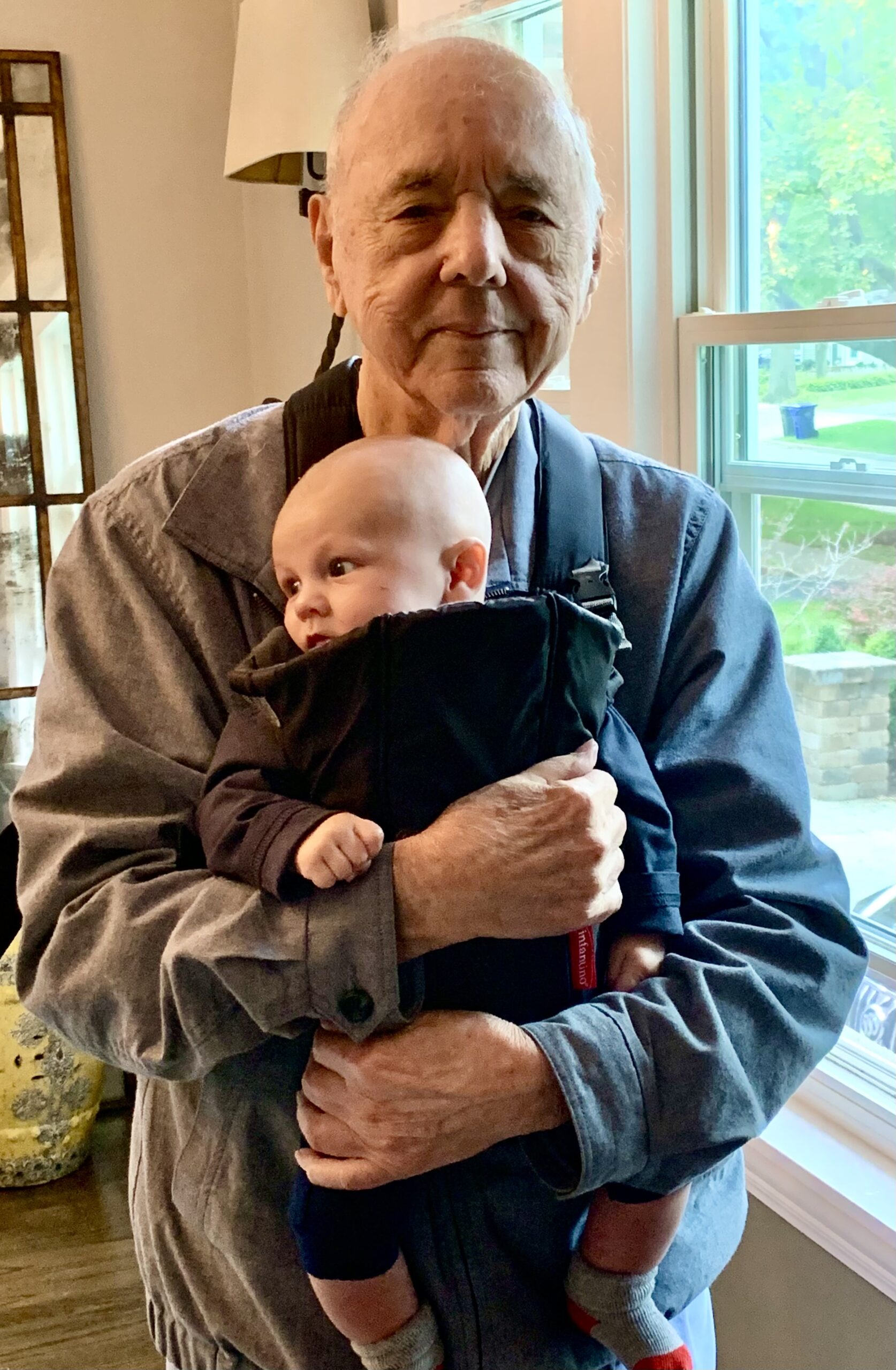

On Saturday, April 1, he reached that goal exactly.

Still exercising five days a week, Emil Garippo looks back on the remarkable century he’s encountered.

“It’s been a good life,” he says in his typically understated tone. “Very good.”

Never planning to be a trendsetter, he has seen and led transformations for decades.

The humble beginnings in childhood

Emil was born in the small flat his parents rented in a poor Little Italy neighborhood, where the University of Illinois/Chicago now sits. The families of both his parents had recently immigrated to the US.

Despite the Great Depression bearing down, he recalls an active, happy life growing up. Playing at Hull House and outdoors, long swims out in Lake Michigan, ballgames with his father where he saw Babe Ruth hit a homer, going home “only to sleep.”

There were the summers at Bowen County Club for underprivileged children. His older brother Mike – a natural leader, Emil says – was head counselor, guiding and supporting the younger children. Back home, Mike looked after Emil and their new sister, Thomasine.

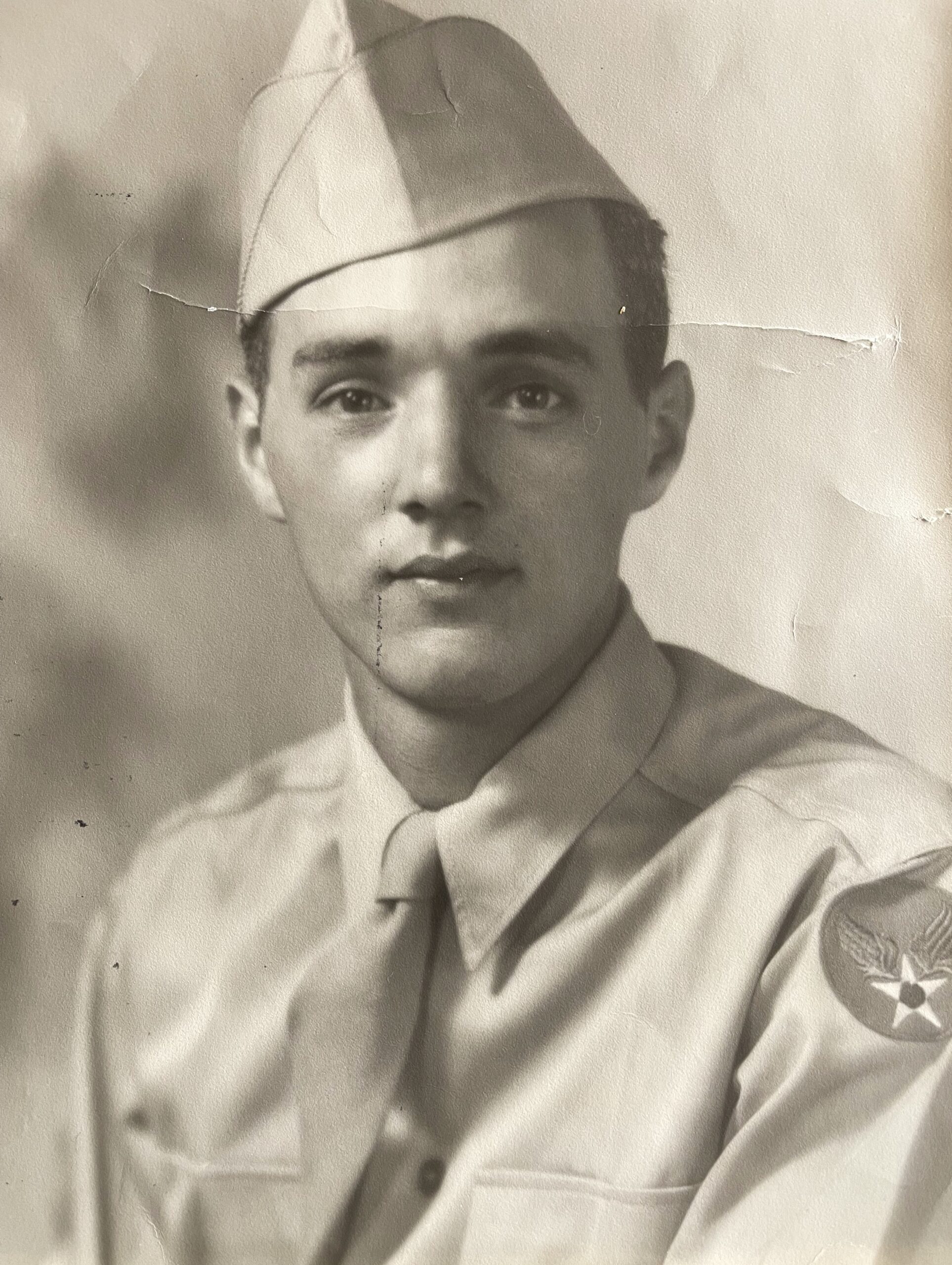

Emil was 18 when bombs began falling on Pearl Harbor. First his brother Mike was sent off, taken from college. Emil’s time to serve came soon after.

In mid-June 1944, he arrived in mainland Europe. Normandy. Downed airplanes with bodies still inside spread along Omaha Beach. Sergeant Garippo then became D+13, military lingo for how long after the D-Day invasion he arrived. As a medic, he still vividly recalls details from the hundreds of bodies he pulled from swamps and fields as he moved east with the military. As well as the comradery and tightness that bonded his unit of 12 comrades.

A painful chapter

Brothers Emil and Mike wrote each other often. But in December 1944, word came. Mike’s courage had led to the capture of 30 German soldiers before he was taken down by enemy fire. He would be awarded the Silver Star, the highest medal for valor not unique to a specific branch. Emil visited his brother’s grave in Holland twice, hitching rides to get there.

Returning to America, he suffered nightmares. But, he says, you just carried on. In the “old neighborhood,” Emil had met the visiting niece of a neighbor. Soon he and Dean Rugg were married. Their son was among the first Baby Boomers. His name: Michael. In the year of his birth, 1948, the family brought the body of his namesake back home to Chicago.

Following his brother’s lead, Emil entered college. He graduated with an education degree from DePaul University in 1949, later earning his Master’s. Doing so, he became among the earliest Americans to benefit from the G.I. Bill and the first in his family with a college degree.

He started teaching in Chicago, rising to assistant principal of Spalding High, one of the nation’s first public schools for children with disabilities. Seeing his talent, the administration brought Emil to the central office to help oversee citywide transportation.

A move to ‘far-off’ Elmhurst

Two daughters came, Deanna then Debbie. Emil befriended a builder who suggested the young family move to then far-off Elmhurst. He again uses “nuts” to describe the reactions of most others to the plan. The area was prairie with just some anticipant roads and sidewalk. But for $11,000 in 1951, he bought his first house there. And within a few years, much of his extended family followed, including his parents and his sister’s family. Today, generations of relatives live in the area, thanks to Emil.

Watching his health

Warned he had a weak heart in the 1960s, Emil read a magazine article that extolled jogging for everyday Americans. Wearing tennis shoes and no special gear, he began running along the local streets, to the astonishment of many of the neighbors. Emil still works out daily, giving himself only weekends off. Twenty minutes on his stationary bike, then a series of yoga-like exercises. He has never undergone surgery and started using a walker and hearing aids only in the last few years. But Emil is no health purist. Before dinner, you might see him mixing a perfect vodka martini today.

Emil’s children talk about the enduring love and support of their parents. In the summers, the family drove literally everywhere in America, to all fifty states. Laughing at the memory, they even recall their dad driving the big family Oldsmobile through Mexico to Acapulco. Just this week, he passed his driver’s test days before becoming a centenarian.

It comes down to family

Emil and Dean were married 74 years. On their 50th anniversary, he wrote a poem calling their union “both adventurous and serene.” For most of their last 20 years, Dean suffered dementia. Emil acted as primary daily caregiver until she passed away at 96 in late 2020.

Emil watches the news and sports every day, but mostly he enjoys time with his children, four grandchildren, and now two great-grandchildren. For little Dylan and Beau he says, “I just want them to have a good life and do the right things.”

Emil doesn’t boast or call attention to himself. But when you talk with him about his life, a playful smile emerges and he admits it.

“I’m always the first guy to do everything,” he said.

And reflecting on the past century: “Everything was beautiful and dangerous and good.”